سلام

ژیاردیا از جمله انگل های مهم زئونوز محسوب می شه که ناشناخته های زیادی در مورد اون و بالاخص نقش میزبان ها و ژنوتایپ اون وجود داره.

در پایین مطلبی در مورد ژیاردیای حیوانات گزاشتم.برای خودم جالب بود.در ذیل اون هم در راستای کار های این روز هام در مورد کنترل بیماری های انگلی در گاو ها مطلب گزاشتم.

دیگه منتظرید چی بگم.

همه چیز گفته شد و بازی تمام شد.

و چون بازی تمام شد تو را کشتند!( بر گرفته از دیالوگ فیلم پنج در پنج فکر کنم).

تا بعد.

Overview of Giardiasis

(Giardosis, Lambliasis, Lambliosis)

Giardiasis is a chronic, intestinal protozoal infection seen worldwide in most domestic and wild mammals, many birds, and people. Infection is common in dogs, cats, ruminants, and pigs. Giardia spp have been reported in 0.44%–39% of fecal samples from pet and shelter dogs and cats, 1%–53% in small ruminants, 9%–73% in cattle, 1%–38% in pigs, and 0.5%–20% in horses, with higher rates of infection in younger animals. Farm prevalences in production animals vary between 0% and 100%, with the highest prevalence in younger animals. The cumulative incidence on a farm where Giardia has been diagnosed is 100% in cattle and goats and nearly 100% in sheep.

Three major morphologic groups have been described: G muris from mice, G agilis from amphibians, and a third group from various warm-blooded animals. There are at least four species in this third group, including G ardeae and G psittaci from birds,G microti from muskrats and voles, and G duodenalis (also known as G intestinalis and G lamblia), a species complex with a wide mammalian host range infecting people and domestic animals. Molecular characterization has shown that G duodenalis is in fact a species complex, comprising seven assemblages (A to G), some of which have distinct host preferences (eg, assemblage C/D in dogs, assemblage F in cats) or a limited host range (eg, assemblage E in hoofed livestock), whereas others infect a wide range of animals, including people (assemblage A and B). There is increasing evidence that some assemblages (A and B) that infect domestic animals can also infect people, although transmission patterns are not totally understood. Dogs have mainly assemblages C and D, cats have assemblages A1 and F, and people are infected with assemblages A2 and B; however, some studies have identified human assemblages of Giardia in canine fecal samples.

Cycle and Transmission

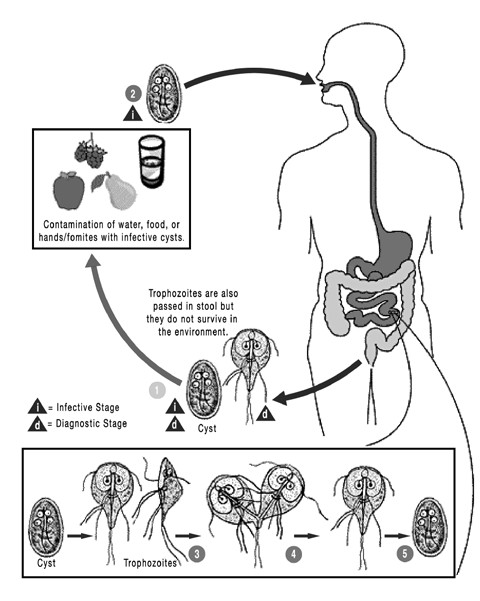

Flagellate protozoa (trophozoites) of the genus Giardia inhabit the mucosal surfaces of the small intestine, where they attach to the brush border, absorb nutrients, and multiply by binary fission. They usually live in the proximal portion of the small intestine. Trophozoites encyst in the small or large intestine, and the newly formed cysts pass in the feces. There are no intracellular stages. The prepatent period is generally 3–10 days. Cyst shedding may be continuous over several days and weeks but is often intermittent, especially in the chronic phase of infection. The cyst is the infective stage and can survive for several weeks in the environment, whereas trophozoites cannot.

Transmission occurs by the fecal-oral route, either by direct contact with an infected host or through a contaminated environment. Characteristics that facilitate infection include the high excretion of cysts by infected animals and the low dose needed for infection. Giardia cysts are infectious immediately after excretion and are very resistant, resulting in a gradual increase in environmental infection pressure. High humidity facilitates survival of cysts in the environment, and overcrowding favors transmission.

Pathogenesis

Giardia infections cause an increase in epithelial permeability, increased numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes, and activation of T lymphocytes. Trophozoite toxins and T-cell activation initiate a diffuse shortening of brush border microvilli and decreased activity of the small-intestinal brush border enzymes, especially lipase, some proteases, and dissacharidases. The diffuse microvillus shortening leads to a decrease in overall absorptive area in the small intestine and an impaired intake of water, electrolytes, and nutrients. The combined effect of this decreased resorption and the brush border enzyme deficiencies results in malabsorptive diarrhea and lower weight gain. The reduced activity of lipase and the increased production of mucin by goblet cells may explain the steatorrhea and mucous diarrhea that has been described in Giardia-infected hosts.

Clinical Findings and Lesions

Giardia infections in dogs and cats may be inapparent or may produce weight loss and chronic diarrhea or steatorrhea, which can be continual or intermittent, particularly in puppies and kittens. Feces usually are soft, poorly formed, pale, malodorous, contain mucus, and appear fatty. Watery diarrhea is unusual in uncomplicated cases, and blood is usually not present in feces. Occasionally, vomiting occurs. Giardiasis must be differentiated from other causes of nutrient malassimilation (eg, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency [see Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency in Small Animals] and intestinal malabsorption [seeMalabsorption Syndromes in Small Animals]). Clinical laboratory findings usually are normal.

In calves, and to a lesser extent in other production animals, giardiasis can result in diarrhea that does not respond to antibiotic or coccidiostatic treatment. The excretion of pasty to fluid feces with a mucoid appearance may indicate giardiasis, especially when the diarrhea occurs in young animals (1–6 mo old). Experimental infection of goat kids, lambs, and calves resulted in a decreased feed efficiency and subsequently a decreased weight gain.

Gross intestinal lesions are seldom evident, although microscopic lesions, consisting of villous atrophy and cuboidal enterocytes, may be present.

Diagnosis

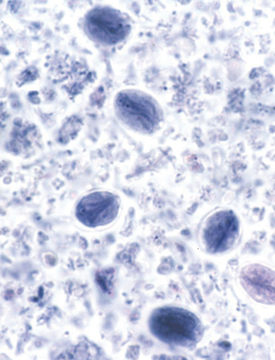

The motile, piriform trophozoites (12–18 × 7–10 μm) are occasionally seen in saline smears of loose or watery feces. They should not be confused with yeast or with trichomonads, which have a single rather than double nucleus, an undulating membrane, and no concave ventral surface. The oval cysts (9–15 × 7–10 μm) can be detected in feces concentrated by the centrifugation-flotation technique using zinc sulfate (specific gravity 1.18). Sodium chloride, sucrose, or sodium nitrate flotation media may be too hypertonic and distort the cysts. Staining cysts with iodine aids identification. Because Giardia cysts are excreted intermittently, several fecal examinations should be performed if giardiasis is suspected (eg, three samples collected throughout 3–5 days). Giardia may be underdiagnosed, because the cysts are intermittently shed.

For the detection of parasite antigen, immunofluorescence assays and ELISA are commercially available. An in-house ELISA available for use in dogs and cats is a useful tool for clinical diagnosis, particularly when coupled with a centrifugal flotation examination of feces. It is best to test symptomatic animals with a combination of a direct saline smear of feces, fecal flotation with centrifugation, and a sensitive, specific ELISA optimized for use in the animal being tested (eg, ELISA for dogs and cats).

Treatment

No drugs are approved for treatment of giardiasis in dogs and cats in the USA. Fenbendazole (50 mg/kg/day for 5–10 days) effectively removes Giardia cysts from the feces of dogs; no adverse effects are reported, and it is safe for pregnant and lactating animals. This dosage is approved to treat Giardiainfections in dogs in Europe. Fenbendazole is not approved in cats but may reduce clinical signs and cyst shedding at 50 mg/kg/day for 5 days. Albendazole is effective at 25 mg/kg, bid for 4 days in dogs and for 5 days in cats but should not be used in these species, because it has led to bone marrow suppression and is not approved for use in these species. A combination of praziquantel (5.4–7 mg/kg), pyrantel (26.8–35.2 mg/kg), and febantel (26.8–35.2 mg/kg) also effectively decreases cyst excretion in infected dogs when administered for 3 days. A synergistic effect between pyrantel and febantel was demonstrated in an animal model, suggesting that the combination product may be preferred over febantel alone.

Metronidazole (extra-label at 25 mg/kg, bid for 5 days) is ~65% effective in eliminating Giardia spp from infected dogs but may be associated with acute development of anorexia and vomiting, which may occasionally progress to pronounced generalized ataxia and vertical positional nystagmus. Metronidazole may be administered to cats at 10–25 mg/kg, bid for 5 days. Metronidazole benzoate is perhaps better tolerated by cats. Safety concerns limit the use of metronidazole in dogs and cats. A possible treatment strategy for dogs would be to treat first with fenbendazole for 5–10 days or to administer both fenbendazole and metronidazole together for 5 days, being sure to bathe the dogs to remove cysts. If clinical disease still persists and cyst shedding continues, the combination therapy should be extended for another 10 days.

Currently, no drug is licensed for the treatment of giardiasis in ruminants. Fenbendazole and albendazole (5–20 mg/kg/day for 3 days) significantly reduce the peak and duration of cyst excretion and result in a clinical benefit in treated calves. Paromomycin (50–75 mg/kg, PO, for 5 days) was found to be highly efficacious in calves.

Oral fenbendazole may be an option for treatment in some birds.

Control

Giardia cysts are immediately infective when passed in the feces and survive in the environment. Cysts are a source of infection and reinfection for animals, particularly those in crowded conditions (eg, kennels, catteries, or intensive rearing systems for production animals). Feces should be removed as soon as possible (at least daily) and disposed of with municipal waste. Infected dogs and cats should be bathed to remove cysts from the hair coat. Prompt and frequent removal of feces limits environmental contamination, as does subsequent disinfection. Cysts are inactivated by most quaternary ammonium compounds, steam, and boiling water.

To increase the efficacy of disinfectants, solutions should be left for 5–20 min before being rinsed off contaminated surfaces. Disinfection of grass yards or runs is impossible, and these areas should be considered contaminated for at least a month after infected dogs last had access. Cysts are susceptible to desiccation, and areas should be allowed to dry thoroughly after cleaning.

GIARDIASIS, DOGS, CATS & PEOPLE

Giardia is a tiny parasite that lives in the intestines of various animals.

Giardia Cyst Trophozoite

Giardia is passed in the feces of animals in the form of a cyst that is resistant to many environmental extremes.

These cysts are scattered through the environment in feces or fecal-contaminated water. These cysts are infectious when passed, and upon ingestion by the next host, the encysted trophozoites emerge from the cysts in the intestinal tract. Within the intestine, the trophozoites feed and multiply. Some trophozoites will then form a cyst wall around themselves, and those cysts will be passed in the feces to continue the cycle.

How Do Dogs, Cats, and People Become Infected?

People and pets rarely share each other’s Giardia

People are typically infected with a human form of Giardia, dogs with a canine form, cats with a feline form, and cattle and sheep with a ruminant form. People are occasionally infected with a different form that is shared with animals. On rare occasions dogs and cats have been found infected with the human form. Thus, there is little evidence for direct transmission from pet dogs and cats to people. However, the rare occurrence of the human forms in cats and dogs means that there may be a slight chance that they pose a risk as a source of human infection.

To be able to distinguish the specific forms, the veterinarian is required to submit samples for specialized tests.

Symptoms of Infection

In dogs and cats, infection with Giardia is usually asymptomatic. Some pets will, however, develop persistent diarrhea. There is usually no blood in the stool.

In people, infection with Giardia also is often asymptomatic. However, some people can develop acute, intermittent, or chronic nonbloody diarrhea. Other symptoms in people include abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and weight loss.

Prevention and Treatment

- Unlike for heartworm disease, there are no drugs that can be routinely given to a pet that will prevent infection.

- Dogs, cats, and people that have symptoms of the infection can be treated; however, there are situations where it is difficult to clear an animal of their infections.

- There are approved drugs for treating the infection in people. These drugs have not been approved for this specific use in dogs and cats, but these and similar drugs are used in them.

Risk Factors for Human Infection

- Accidentally swallowing Giardia cysts from surfaces contaminated with feces, such as bathroom fixtures,changing tables, diaper pails, or toys contaminated with feces.

- Drinking water from contaminated sources (e.g., lakes, streams, shallow [less than 50 feet]or poorly maintained wells).

- Swallowing recreational water contaminated with cysts. Recreational water includes water in swimming pools, water parks, hot tubs or spas, fountains, lakes, rivers, springs, ponds, or streams that can be contaminated with feces or sewage.

- Eating contaminated uncooked, fresh produce.

- Having contact with someone who is infected with Giardiasis.

- Changing diapers of children with Giardiasis

- Traveling to countries where Giardiasis is common and being exposed to the parasite as described above.

The Companion Animal Parasite Council

The Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) is an independent council of veterinarians and other heath care professionals established to create guidelines for the optimal control of internal and external parasites that threaten the health of pets and people. It brings together broad expertise in pararsitology, internal medicine, human health care, public health, veterinary law, private practice and association leadership.

Parasite Control for Cow Calf Operations

Spring is coming and with calving season underway it is important to keep our eyes forward on to the next step in production. Grass turnout in the spring is the most common secondary benchmark of the year. With grass turnout comes exposure to parasites that have overwintered either in the pasture or in the cattle themselves. Use of dewormer compounds can significantly improve the average level of production; however, care must be taken to avoid a buildup of resistant populations. A short list of deworming drugs can be seen in Table 1. Important differentiations between drugs include the overall effect on the larval state of internal parasites, the effect on external parasites, and the route of administration. General recommendations regarding the use of these drugs should be discussed with your herd veterinarian and in compliance with the label claims of your product. The rest of this article will cover some types, symptoms and treatments of common parasites (Table 2) as well as general best management practices and ideas to be used on your farm or ranch for parasite control.

Table 1. Dewormer Drug Examples for Stomach & Intestinal Worms

| Drug Class | Active Drug | Effective Against Adults | Effective Against Larvae | Common Routes of Administration |

| Benzimidazole | Albendazole | Yes | Yes | Oral Drench |

| Fenbendazole | Yes | Moderate | Oral Drench | |

| Oxfendazole | Yes | Yes | Oral Drench | |

| Imidathiazole | Levamisole | Yes | Moderate | Pour-on, Oral Drench, Injectable |

| Morantel | Yes | No | Bolus, Crumbles | |

| Avermectin | Ivermectin | Yes | Yes | Pour-on, Oral Drench, Injectable |

| Doramectin | Yes | Yes | Pour-on, Injectable | |

| Moxidectin | Yes | Yes | Pour-on, Injectable | |

Table 2. Cattle Parasites of Primary Concern

|

Internal Parasites |

||

| Parasite | Symptoms of Infestation | Treatment |

| Brown Stomach Worm (Ostertagia ostertagi) |

Diarrhea, anemia, slow growth | Any of the above anti-parasitics. *Cattle develop resistance to worm infestations slowly. Cow’s older than 3-4 years should not require maintenance dosing. Weaned calves and heifers are the most affected. Watch for resistance. |

| Cooperia | Diarrhea, in-appetent, slow growth | |

| Haemonchus | Anemia, slow growth | |

| Trichostrongylus | Diarrhea, slow growth | |

| Nematodirus | Diarrhea, slow growth | |

|

External Parasites |

||

| Parasite | Symptoms of Infestation | Treatment |

| Lice | Hair loss, scrapes, discomfort | 2 to 3 topical treatments separated by 2-3 weeks with ivermectin (be careful if your herd has a history of grubs) or topical insecticide |

| Mange | Hair loss, ulcers, discomfort, secondary infections | Topical insecticides,*work with your veterinarian as mange organisms are reportable infestations in the US |

| Grubs | Warbles (larval heel flies) appear in the spring along the backs of animals. Painful. | In the Fall, systemic ivermectin or an organophosphate to kill migrating larva. *Do not apply systemic insecticides in the winter or early spring, can cause paralysis and/or bloat |

Route of Administration:

There are many ways that products can be administered to cattle with the most common methods including: topical pour-on (with or without systemic absorption), injectable, and oral drenches. For treating internal parasites, injectable products and oral drenches ensure delivery of the desired dose of drug. Pour-on products can be effectively absorbed systemically and provide a good dose; however, there is more variability, especially if the weather does not cooperate. The most important aspect to ensure is that each animal receives an adequate dose based on its body weight, regardless of the route of administration. Basing the dosage off of body weight helps attain the best efficacy, as under dosing will not eliminate all the parasites while promoting resistance, and overdosing can be harmful to the animals and an unnecessary expense.

Rotation of Product:

Resistant parasite populations develop over time from repeated use of the same deworming products. The more frequently a dewormer is used, the quicker that resistance will develop. Monitoring effectiveness of treatment can help you determine if and when switching products is necessary.

Monitoring Treatment Effect:

If you are concerned about how well your current deworming protocol works, you can work with your veterinarian to perform a fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT). This test consists of evaluating the baseline level of parasite egg shedding in your herd, applying your standard deworming strategy, and then rechecking the level of egg shedding in your herd. If a deworming compound reduces the fecal egg count by more than 95% the dewormer works well. If the reduction is less than 95% there is resistance in your herd. As a reminder to veterinarians, best practices indicate conducting the FECRT on paired samples from individuals in the herd.

Herd Populations Most at Risk:

Cattle build up resistance to parasite infestations slowly and younger animals are more at risk of clinical disease. The most important populations to manage for parasites are weaned calves, heifers, and 2nd calf cows. Older cows have had the opportunity to develop resistance and should not require annual or semiannual treatment in the absence of clinical signs, work with your herd veterinarian to figure out a parasite control strategy that fits your situation.

Other Management Strategies:

Pasture management through rotation, alternate species grazing, haying, and rotational tillage can significantly reduce the number of infective larvae on a pasture. Focused deworming of individuals showing clinical signs of parasitism (diarrhea, anorexia, high fecal egg counts, etc) rather than mass treatment of groups can be very effective in promoting overall herd performance, reducing the development of resistant parasites, all while reducing the level of contamination of pasture. By only treating animals that are most affected we leave a population of parasites in the less affected animals that have not been exposed to the anti-parasitic drug. This population of susceptible parasites in the animals and environment are called refugia, and can lengthen the time that anthelmintic drugs will be effective. However, if mass treating in the spring, the use of a persistent product (check labels for duration of residual effect) for parasite control should be used to decrease new fecal shedding and pasture contamination. This treatment should be done as late as possible in the spring and up to 4-6 weeks after grass turnout to help limit infestation rates in calves. As a last thought, maintaining appropriate stocking densities to prevent overgrazing can also help limit parasite exposure.

The best way to manage parasites in your herd will be unique to your situation. Hopefully this article has given you a better understanding of current issues and your management options. Please contact your herd veterinarian, SDSU extension cow-calf specialists, SDSU extension veterinarian, or Joe Darrington with questions.

References:

- Smith, B.P., 2009, Large Animal Internal Medicine 4th Edition, Mosby Elsevier Publishing

- FDA CVM, 2015, List of Approved Animal Drugs.

Used with permission and written by: Joe Darrington, SDSU Extension Livestock Environment Associate

SDSU Agricultural & Biosystems Engineering Department, and Taylor Grussing, SDSU Extension Cow/Calf Field Specialist. article orignally appeared at SDSU igrow.org website